Article – The numbers tell a story that many Calgarians had hoped was relegated to history books. Alberta is facing its worst measles outbreak in nearly four decades, with cases surging to levels not seen since 1986. As a journalist who’s covered health crises in our city before, this development feels both alarming and frustratingly preventable.

Last week, I sat down with Dr. Karla Nelson at the Sheldon Chumir Health Centre, who didn’t mince words about our current situation. “What we’re seeing isn’t just concerning—it’s a public health emergency that could have been avoided,” she told me, gesturing toward a chart showing the climbing case numbers across the province.

The Alberta Health Services dashboard now reports 18 confirmed cases province-wide since January, with 7 of those right here in Calgary. To put this in perspective, between 2013 and 2023, Alberta averaged fewer than 3 cases annually. This exponential jump has health officials scrambling.

Walking through the Beltline yesterday, I noticed posters about vaccination clinics appearing in community centers and coffee shops—visual evidence of how seriously officials are taking this outbreak. These impromptu clinics represent just one part of the public health response that’s rapidly expanding across our city.

“The concerning part isn’t just the number of cases,” explains Dr. Mark Richardson, infectious disease specialist at the University of Calgary. “It’s how quickly the virus is spreading in communities with lower vaccination rates.” Richardson points to immunization data showing certain Calgary neighborhoods with vaccination rates below 80%—well under the 95% threshold epidemiologists consider necessary for effective community protection.

The City of Calgary’s emergency management team has begun coordinating with provincial health authorities to establish additional vaccination sites, particularly in areas with lower immunization rates. Schools in affected zones have implemented enhanced screening protocols, with some considering temporary remote learning options for unvaccinated students if cases continue rising.

This outbreak exists within a broader national context. The Public Health Agency of Canada recently issued an alert about increasing measles activity across multiple provinces, with cases appearing in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec. However, Alberta’s numbers represent a disproportionate share of the national total.

Local business owner Jasmine Kang, whose daycare in Kensington had to temporarily close after potential exposure, shared her frustration. “We’ve spent years navigating COVID protocols, and now we’re dealing with a disease that was practically eliminated years ago. The financial impact on small businesses like mine is substantial.”

The resurgence of measles reflects a troubling trend I’ve observed covering health stories across Calgary: vaccine hesitancy has been growing steadily in certain communities. Dr. Nelson attributes this partly to misinformation spreading through social media and partly to complacency. “When diseases disappear from public view, people forget why we vaccinated in the first place,” she noted.

Alberta Health Services has launched an awareness campaign emphasizing that measles isn’t just a childhood rash but a potentially dangerous disease. Before widespread vaccination, it was a leading cause of childhood blindness and mortality worldwide. The highly contagious nature of the virus—capable of spreading through airborne particles that remain infectious for up to two hours—makes containment particularly challenging.

For concerned parents like Michael Dorian, whom I met at a Riley Park playground supervising his two young children, the outbreak has prompted renewed attention to immunization records. “We verified our kids’ vaccination status immediately after hearing about the first cases,” he said. “But it’s frustrating knowing other families aren’t doing the same, putting everyone at risk.”

Calgary’s healthcare infrastructure, still recovering from the strain of COVID-19, faces new pressures with this outbreak. Emergency departments report increased visits from concerned parents whose children show potential symptoms—fever, cough, runny nose, and the telltale red rash that typically appears 3-5 days after initial symptoms.

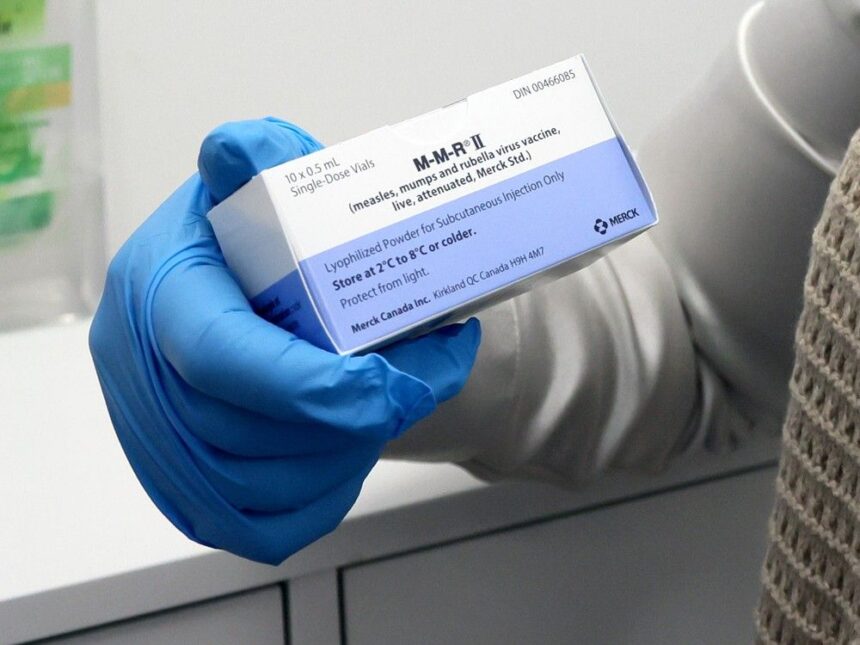

Dr. Richardson emphasizes that vaccination remains our most effective tool against further spread. “Two doses of the MMR vaccine provide approximately 97% protection against measles. For those unsure of their vaccination status, there’s no harm in receiving another dose.”

City Councillor Jasmine Wong told me the city is exploring additional support measures for affected communities. “We’re considering mobile vaccination clinics that can target areas with lower immunization rates, similar to successful models we used during COVID.”

As we navigate this unexpected public health challenge, I’m reminded of how quickly we can slide backward without vigilance. The measles virus, eliminated from Canada in 1998 through comprehensive vaccination programs, has found footholds in communities where immunization rates have fallen.

The path forward seems clear, if not simple: renewed commitment to evidence-based public health measures, expanded access to vaccines, and honest conversations about the real risks of vaccine-preventable diseases versus the minimal risks of immunization.

For now, health officials urge Calgarians with symptoms to call Health Link at 811 before seeking in-person care, to minimize potential exposure to others. And for those uncertain about their vaccination status, now is the time to check and update immunizations through Alberta Health Services.

After covering Calgary’s health stories for nearly fifteen years, this outbreak serves as a stark reminder that public health victories require ongoing commitment—not just from officials and healthcare providers, but from all of us as community members.